The Jesus who we encounter as a distinctive phenomenon in the haze of ineffable religious experience is mediated by a retrojected interpretation of the radical prophet and mystic of Nazareth in light of the resurrection. This retrojection is a reversed historical projection: the identity of Jesus is established by his return from the realm of death into the sphere of the living and ascension into the life of God

by his birth. The assembly of his life-events construct a portrait that resurrection completes, producing what we call the

. Jesus only finds a singular identity within the totality of this event.

So what fundamentally occurs in the Christ Event? This question is primarily phenomenological, i.e. it concerns itself with the social impact and personal/experiential significance of the event. I will attempt to answer this through the categories of alienation, mediation, and participation.

I. Alienation

In Paul's Adamic interpretation of the Christ Event, we find binaries of obedience vs disobedience, old man vs new man, etc. What we can retrieve from this is the fundamental distinction between two kinds human beings, primal and eschatological, as well as the role of the Christ Event in making the transition.

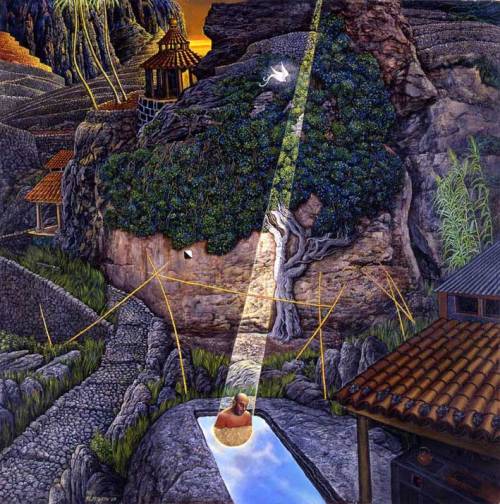

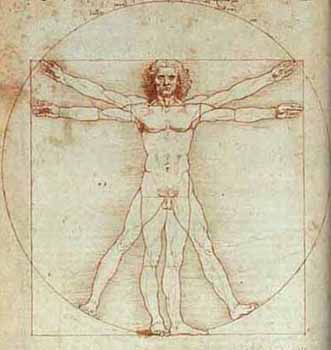

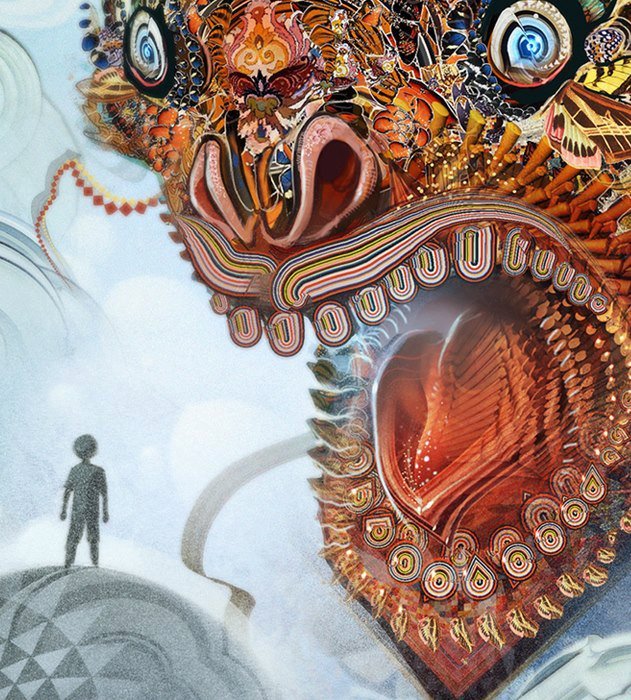

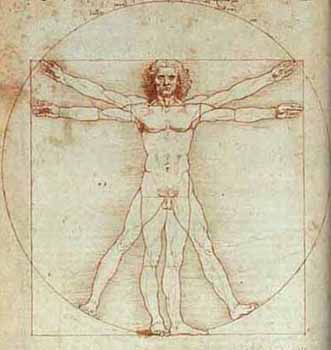

The primal human is the original human prototype of evolution, along with all of his/her imperfections and deficiencies. This type of human is caught in between the ground and the sky. Animals walk on all fours and belong to the earth. Angels have wings and inhabit the heavens. Humans walk upright and bridge the gap. They are caught in between two spheres of existence. They are also genetically caught in between base instincts and transcendence. Our base instincts, inherited from the sphere of basic organic and sentient lifeforms, demand that we protect ourselves, feed ourselves, survive, reproduce, perpetuate, and guard our own. This is predicated on natural selection and "survival of the fittest," paradigmatic of nature as "red in tooth and claw." On the other side, our drive toward transcendence is rooted in the emergence of self-consciousness, intersubjectivity, and awareness of the distinctions between things, others, and the finite & Infinite. We naturally tend toward the Infinite. Knowing we are finite, we experience a fundamental sense of alienation, caught between our animal finitude and our tendency toward transcendental integration with the Infinite (which is theologically personified as God). Unfortunately, the majority of efforts made by primal humanity to transcend their finitude have resulted in nothing more than the will to power--institutionalized by religion, legitimated in theology (through the ideological projection of grandiose images of the human ego onto God), and fully rooted in base instincts. Thus, our efforts toward escaping alienation have only doubled it over on itself.

In contrast, the eschatological human is the human being who has successfully transcended the animal sphere and achieved the actualization of human desire in distinction to base instinct. The fundamental paradigm of incarnation in the New Testament establishes the identity of Jesus as the eschatological human through the unfolding events of his life that culminate in the resurrection, i.e. transcendence beyond finitude. The accomplishment of transcendence that culminates in the resurrection begins to unfold in the activity of Jesus' life and can be described within the category of mediation.

II. Mediation

Jesus has always been understood in Christian thought as a

mediator between God and humanity. Unfortunately, Western Christianity has couched this term in legal metaphors, almost always interpreting "mediator" as one who defends another in court. However, Jesus is enabled to mediate through

incarnation in the New Testament. Thus, it is important to begin with a brief overview of the meaning of incarnation before explaining what

mediation means.

Recalling that Jesus' identity as the incarnate Son of God only comes together within the totality of his being and activity, affirmed and consummated in resurrection, incarnation cannot begin with a narrowed focus on the particulars of Jesus' birth or even the descension/condescension of the Divine presence onto him at his baptism by John. Both of these are useful as symbols, whether true or not, but they do not demonstrate how Jesus' identity ultimately came together in the memories of his followers. Without the resurrection they would have regarded him as just another failed Messiah. The resurrection retrojects an incarnational understanding onto Jesus in conjunction with his vocational activity: the resurrection, affirming the embodiment of the Divine presence in Jesus, reinterprets his words and actions as

demonstrations and

manifestations of that presence. Thus, Jesus incarnates (i.e. puts into flesh and blood) the Divine character.

The central metaphor for incarnation retrieved from the New Testament is the Logos of the opening poem to John's Gospel. The Logos is the divine principle that binds the cosmos together, the mediating logic within reality, the ground of order and form, and the "world-soul." The proclamation that the Logos has become present in Jesus borrows literary themes and terminology from Jewish wisdom literature, associating the Wisdom of God in Jewish literature (personified as a woman) with the Logos of Greek philosophy/cosmology. Paul also refers to Jesus as the Wisdom of God. The question then becomes, what is this wisdom?

Paul refers to this wisdom as weak and foolish in this world. He categorizes the world (better trans. as age), or the realm of darkness, as greedy, murderous, selfish, and hedonistic. He quantifies the Divine character through what he calls the fruit of the Spirit, which include generosity, self-control, and love. Jesus radically practices these virtues throughout his life, abandoning the ego/will-to-power in favor of loving everyone (including enemies) and generously giving to the needy. This is the wisdom of God mediated through Jesus by the Divine presence in him.

This incarnation/mediation is only made possible when Jesus distinguishes himself from God -- not my will but your will be done, not my will but my Father's will -- so that in obedience toward God, recognizing his creaturely finitude before the Infinite, he may

participate in the Infinite life and consequently mediate it -- when you have seen me you have seen the Father, I and my Father are one.

Thus the human body of Jesus is a finite, creaturely temple for the Infinite life to dwell and empower, enabled when the creature recognizes its own finitude and self-distinction in perfect obedience and submission to the will of God--summed up in the character of Divine wisdom.

III. Participation

Jesus incarnates the Way -- the new existential mode of being for humanity, constituted by obedience to Divine wisdom and grounded in a basic re-cognition of finitude and creaturely distinction before the Holy ineffable Infinite. This is the new existential mode of being-in-the-world for the eschatological human being, enabled by two distinctions: the humble self-distinction of the creature from the Creator and, consequently, the new distinction of the eschatological human being from the primal human being. The self-distinction of the creature from the Creator is a reversal of primal humanity's deficiency--symbolized by Eve and Adam's downfall through their will-to-power and desire to erase this distinction. This reversal accomplishes the creation of the eschatological human being. Christians hold that Jesus accomplishes/inaugurates this through perfect(ed) self-distinction. Jesus, in the full acceptance of his finitude and in submission to the Infinite ground of his being, imitated the love of God by extending it to others, thus eradicating horizontal alienation.

To participate in Jesus' way of being-in-the-world is to act in the absolute dependency that saturates the open-minded consciousness, to walk in that humility before other humans and God, and to imitate the love of God as disclosed in the historical activity of Jesus Christ. This mimetic participation (

mimesis=imitation of human action) in Jesus' existential mode of being is the re-enfleshment of the Logos embodied by Jesus--that is, the Logos that is the world-principle of unifying love and creativity. This re-enfleshment of the Logos constitutes another

body of Jesus, the

body of Christ spoken of by Paul. Thus the human community as the body of Christ is the eschatological community -- a taste of the new creation that is always arriving from the future into the present. The human community's re-embodiment of Jesus' way of being is symbolized in the church's centering sacrament -- the Eucharist. The bread and wine are the body and blood of Jesus Christ transformed into a new ontological existence. As Paul says, because the whole community eats of this one bread and drinks of this one cup, they are all one body and one blood. Again, the Logos as a world-principle of unifying love is at work here, realized and actualized by the community as a preview of its creative transformation of the cosmos in the future. This unification saves us absolutely from our primal alienation by bringing us into a recognition of absolute dependency, finitude, and self-distinction that opens us up to God and the Other in such a way that we must relate and therefore love. This is a freedom

from independence into interdependence predicated by mutual embrace. The Christ Event then can also be called the Eucharistic Event that repeats itself through our mimetic participation of the way of Jesus yielding the re-embodiment of the world-principle of unifying love. Thus the Eucharist is salvific, enabling our transcendence by inviting us into the mutual embrace of the Trinitarian community.

IV. The Eucharistic Axiom

Eucharist

Eucharist consists of a conjunction of the Greek

Eu meaning "good,""well-being," or "happiness," and

charis meaning grace or "gift." Thus the Eucharist in the joy of the Gift, the goodness of the Gift, our well-being in relation to the Gift. This Gift is the Gift of Presence. This Presence is the Divine Presence that we discover in the healing of our alienation and experience of unifying love and mutual embrace. Thus Divine Presence incarnates itself in human presence by unifying humans together. The joy of the Gift of Presence is the joy of the Gift of Love in human community, healed of its division, pride, and violence.

If we begin with the Eucharist and look at how it re-organizes and re-rationalizes our world, we will discover the foundation, axiom, and promise of a future and a hope beyond our always schizophrenic ways of being that opens up other possible worlds in which grace and love transform and nourish human life. We will discover the unfolding of a new destiny for human beings in relation to the unconditional love that holds this world together.

V. Conclusion

What we can conclude is that Jesus' identity follows and is

constituted by his agency and not the other way around. In other words, Jesus' agency and activity culminating in the self-sacrificial love of the cross constitute his identity as the mediator/embodiment of the full Presence of the Logos that is the world-principle of unifying love that takes form in his way of

being-in-the-world. This allows him to carry forth a salvation into the world that rescues us from our alienation and brings us into humble fellowship with other creatures through our mimetic participation in his way of being. This new way of being constitutes a new kind of humanity -- the eschatological human being.